Gear Institute faculty member Matt Samet, of Boulder, Colorado, has been climbing for a quarter century, and is the former Editor of Climbing Magazine, and the author of the Climbing Dictionary (published 2011), an alphabetical climber-slang dictionary and historical survey of the sport illustrated by Mike Tea.

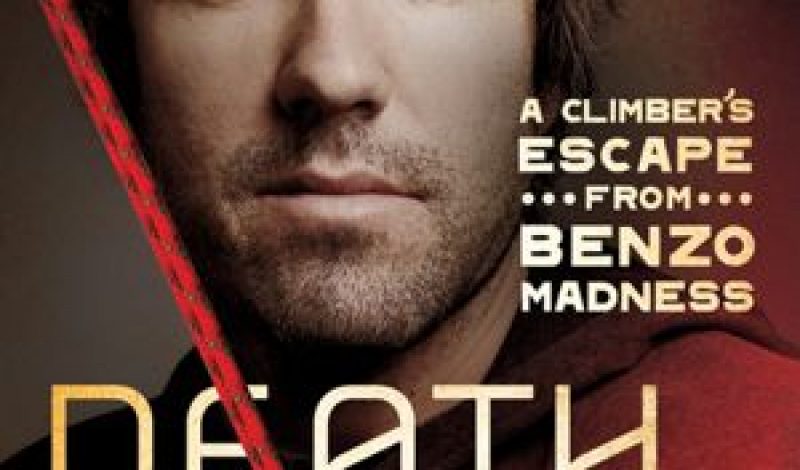

His new book, Death Grip (which will be officially released on Feb. 12) chronicles his near-fatal struggle with anxiety and depression, and his nightmarish journey through the dangerous world of prescription drugs. Although Samet lived to climb, his depression, compounded by the extreme diet and fitness practices of climbers, led him to the world of psychiatric medicine, where he developed a dangerous addiction to prescribed medications. We asked him about the book, and how hard it was to tell his story.

Gear Institute: Matt, you cover some pretty rough—and personal—battles in this book. What was it like actually putting all this into words?

Matt Samet: Basically, terrifying. We’ve had a few advance readers to help with promotional blurbs, and I felt a creeping sense of dread having the book in their hands while they read it, but the feedback so far has been positive. I suppose the upshot is, for every one person that reads this book and condemns it as yet another scabrous, navel-gazing junkie confessional, perhaps four others battling with dependence on benzodiazepine tranquilizers or psychiatric over-prescription will read Death Grip and see their story in my own, as well as the fact that there is hope and a way out. I was once a desperate, dead-end, multiple-diagnosis, over-medicated toxic sewer, but as soon I put enough time between me and the meds and the shrinks, I got better: better than I ever could have imagined. I never needed the pills in the first place.

GI: You’ve built your career writing about climbing. How did that prepare you for covering the other aspects of psychology and biography?

MS: I don’t think I’ve ever been the best climbing writer, but I’ve been at it awhile and devour as much climbing literature as I can to see how other writers go about storytelling, which is what I tried to do with Death Grip: focus on the story. Like a rollicking, white-knuckler climbing tale, I wanted to keep the reader in the action and focusing on those crazy, microscopic details you notice in the grip of fear, be it in the mountains or, as in the memoir, in the psycho-spiritual hell of tranquilizer withdrawal. That’s what our brains latch onto under extreme duress: that green patch of fuzzy lichen when you’re free-soloing 500 feet up and get gripped, or the black hairline seams between the linoleum tiles of some purgatorial psychiatric ward.

GI: Do you see a clear parallel between climbing tough routes and dealing with mental health issues, and if so, how?

MS: I think there is—both ultimately come down to mind control and to knowing yourself. In other words, to escape the clutches of a difficult death lead or to blaze through the fog of a thick depression, it helps to pose to yourself a few difficult questions:

1) Why am I here (or how did I get here)?

2) Do I like being here and can I stay here?

And 3) What do I need to do to get out of here before things get worse?

If you can ask and truthfully answer these three fundamental questions, you can often declaw your fear and stop it from bollixing your decision-making process. From there, you take steps to extricate yourself. On the rock, that might mean downclimbing to place another cam before that long runout that started your eyes bugging and legs quaking. With a bad mental/emotional spell, as with depression and panic attacks, that might mean looking at the ways you’re self-sabotaging, and cleansing your life of any negative influences: a crappy job, an abusive relationship, a stressful commute, whatever.

Or it might simply mean kicking yourself in the ass and going for a walk, even if you don’t feel like it—just getting in motion until you feel some sense of purpose again. For years, however, I fled these questions, which is certainly the broken thinking that led me to seek a solution to “chronic anxiety” in drugs, psychiatric diagnoses, and prescription pills.

I also think being a climber helped with healing from the damage done by addiction and psychiatric medicines. On a hard route, you un-self-consciously slip into the zone; you’re exerting yourself so intensely and focusing so hard on minutiae like individual foot crystals and which two fingers you’ll grab that next hold with that your ego drops away. You no longer have a sense that any “you” exists outside of pure doing: action.

GI: What do you hope this book means to readers?

MS: I hope that it helps people to see that fear and darkness need not rule their lives, and that running from them, like I did, will destroy you in the end. And also that anxiety and depression are ultimately useful tools: teachers and forces for positive change, if you stop to listen to them. One of the most depressing things about modern life is this overwhelming need people have for their emotional problems to be black and white: a search for a rubric, an official diagnosis as to why we feel the way we do, and the attendant prescription for whatever pill to make the “problem” go away. As if this provides some sort of reassurance about anything.

But on a purely philosophical level, we have always experienced darkness and bleakness and pain and angst. Anyone who’s lost a loved one will tell you this; anyone who’s had a chronic illness or been physically victimized will tell you this; any good Buddhist will tell you this. Life is change and entropy and upheaval and suffering, and then we die, and ultimately there is no reason. We have no idea why we’re here nor can we, but it’s in the struggle that meaning emerges.

GI: How would you like to see your story complement the canon of climbing literature?

MS: Hah, number-one New York Times bestseller, of course! More seriously, I suppose I hope that it will end up in the vein of other books of a more traditional, physical life-and-death struggle, such as Touching the Void or The White Spider or Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Most of my battles were fought in psych wards or in silent, lonely bedrooms quaking atop the sheets, but it was an epic fight nonetheless. In all these books, the undercurrent is a desire to live, a flame that burns very brightly in climbers for as much as we deliberately place ourselves in harm’s way.

Order the book here.